From Research to Belonging: How Oral History Helped Me See Zarqa Anew

Hamza Khawaldeh

من البحث إلى الانتماء: كيف جعلني التاريخ الشفوي أرى الزرقاء بعيون جديدة

حمزة الخوالدة

“صرت أقدّر جدتي أكثر … وصرت أشوف الزرقاء بعيون جديدة”

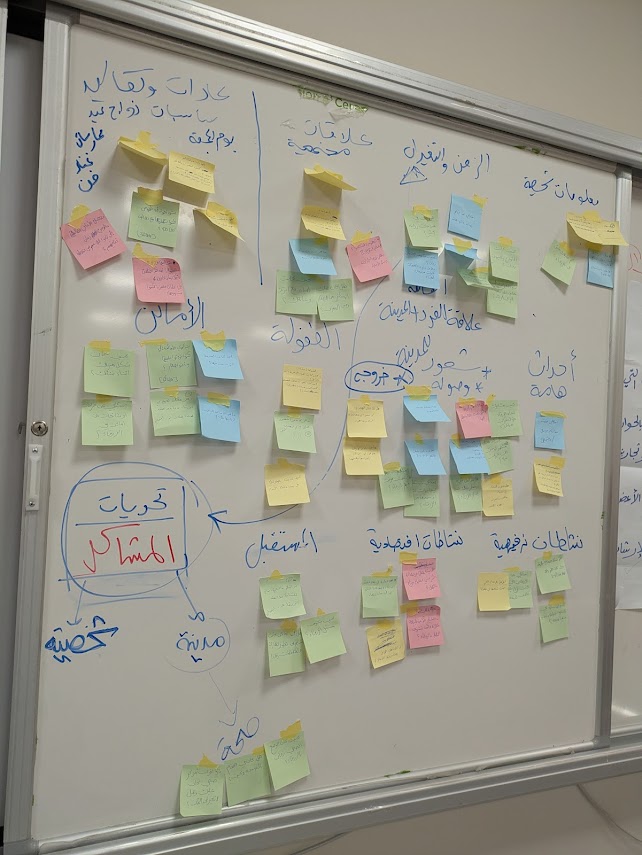

أنا حمزة الخوالدة، أحد المشاركين في مشروع “ضوء على الزرقاء”، وأعمل ضمن فريق من الباحثين الشباب والشابات على تدوين التاريخ الشفهي للمدينة. ركّزت التدريبات التي تلقيناها طوال العام الماضي على أساليب البحث، تعلمنا فيها طُرق إجراء المقابلات، وكيف نكتب الأسئلة بشكلٍ تشاركي. كما تعلمنا تقنيات طرح الأسئلة على الضيف، وكيفيات إدارة الحوار، بما يجعل حديثنا معه منسابًا، والسرد منفتحًا. لم أتعلم من هذه التدريبات المسائل البحثية تقنية فقط، بل فتحت الباب للحظات تعلم شخصية عميقة. أتناول في هذه المدونة مجموعة من الملاحظات والتأملات عن أثر عملي باحثًا في هذا المشروع على نظرتي للمدينة ولدوري فيها.

لقد أتاح البحث في تاريخ مدينتي الشفهي إدراك مركزية الحياة اليومية في فهم المدينة وتحولاتها. وتعلمت أن قصص الناس ليست مجرد حكايا عابرة، بل مرآة تعكس تاريخ المدينة على نحوٍ حي وحميم. أحد هذه الملاحظات كانت حين بدأنا إجراء المقابلات مع أهل الزرقاء، ووجدنا أنفسنا نناقش أدوار النساء، وأثرهن غير المعترف به في الحياة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية للزرقاء. وبعد جولات ميدانية ومقابلات شفوية طويلة، وجدت نفسي أقول: “والله صرت أقدّر جدتي أكثر”.

لم أكن أدرك كم كانت جدتي أم عمار، والدة أبي، تبذل جهدًا مُضنيًا لتلبي احتياجات عائلتها اليومية. أصبحت أرى نشاطاتها بطريقة مختلفة، وانتابتني مشاعر امتنانٍ شديدة للجهد اليومي الذي كانت تبذله. وُلدت جدتي في أربعينيات القرن الماضي، وتعلمت من أمها مهارات الزراعة والرعي وإدارة البيت. كانت تزرع القمح والشعير، وتحصد السنابل، وتعدّ المونة لفصل الشتاء. سمعت من والدي عن قصص تروي كيف كانت تستيقظ قبل الفجر، لتقطع مسافات طويلة لتسحب الماء من الآبار، ثم تجمع الحطب، وتخبز على الصاج. وكيف كانت تصنع الخيام من الصوف الذي تنسجه بيديها. عندما انتقلت إلى الزرقاء، احتفظت بمهنة الخياطة، وكانت تخيط الحقائب، وتساعد جيرانها، وتشارك جدي في التجارة، واشترت ثلاث “منوحات” لتأمين الحليب لأبنائها. كانت حياتها مليئة بالعطاء والاستمرارية، دون أن تنتظر أي مقابل أو تقدير. لقد أدركت أن الأدوار النسائية، رغم عدم توثيقها أو الاحتفاء بها، أو أحيانًا النظر بدونية لها، تشكل الأساس الذي تقوم عليه حياتنا الاجتماعية. اكتشفت بأنهن شاركن على نحو حقيقي في بناء هذه المدينة، ليس فقط في الماضي، بل في الذاكرة الحية التي نحاول اليوم إعادة سردها.

أما الملاحظة الأخرى التي أود الحديث عنها، هي تأثير موقعي من البحث على ديناميكيات سير المقابلات التي كنت جزءًا منها. بصفتي فردًا من أبناء قبيلة بني حسن، كان ذلك يفتح مساحات جديدة لم تكن لتحدث لو لم أكن موجود، مما كان يفرض عليّ مسؤولية مضاعفة في الإصغاء. كثيرًا ما وجدت نفسي في لحظات كثيفة، أتنقل بين الاستماع، وأطرح الأسئلة باعتباري محاورًا، إلى المراجعة والتأمل بصفتي فردًا من أبناء هذه المدينة. لم تكن المقابلات مجرد جمع بيانات فحسب، بل لقاءات تنعكس عليّ شخصيًا، وتدفعني للتفكير في هويتنا الجماعية. كانت تدفعني لأن أرى الزرقاء في كليتها، بشكل غير منحصرٍ ضمن نطاق عشيرتي، بل شاملٍ لكل أبنائها، الذين يحملون خلفيات وتاريخًا طويلًا مشتركًا رغم اختلافاتهم وتنوعهم.

في بداية المشروع، كنت أرى نفسي ببساطة كأحد أفراد قبيلة بني حسن المقيمين في الزرقاء، دون أن أربط هذا الانتماء بسياقه الأوسع. لكن مع مرور الوقت، ومع كل مقابلة، بدأت أتتبع جذور عشيرتي، وأتعلم عن دورهم في الزراعة والاستقرار، وكيف تعايشوا مع الشيشانيين والفلسطينيين والعشائر الأخرى. فتح هذا الفهم أفقًا جديدًا، جعلني أرى الانتماء ليس مجرد كلمة أو هوية سطحية وضيقة، بل هو بناء معقد مليء بالمعرفة والسياق والتاريخ المشترك الذي يربطنا جميعًا. أصبح الانتماء بالنسبة لي شيئًا حيويًا ومترابطًا، يتشكل عبر تجاربنا المشتركة في بناء المدينة.

دفعني المشروع للتأمل بعمق في علاقتي بالمدينة. لم أعد أراها مجرد مكان أعيش فيه، بل أصبحت بالنسبة لي نسيجًا حيًا ومتعددًا، يُعاد اكتشافه كل يوم من خلال قصص الناس الذين يعيشون فيها. شعرت وكأنني أصبحت شريكًا في هذه المدينة، لا مجرد فرد فيها، وأصبحت مسؤوليتي أكبر من مجرد الانتماء لعائلتي أو عشيرتي، بل امتدت لتشمل تاريخًا جماعيًا وثقافةً غنية تعيش بيننا جميعًا.

“I began to appreciate my grandmother more… and I started seeing Zarqa with new eyes.”

My name is Hamza Al-Khawaldeh. I’m one of the youth researchers in the “Surfacing Zarqa” project, working alongside a team documenting the oral histories of the city. Over the past year, we received training in qualitative research methods. We learned how to conduct interviews, formulate questions collaboratively, guide conversations, and ask follow-up questions that create open, flowing dialogue. But the process wasn’t only about technical skills; it became a space of personal transformation. In this blog, I share reflections on how being part of this project reshaped the way I see Zarqa and my place within it.

Oral history allowed me to recognise the everyday as central to understanding the city and how it has changed. People’s stories are not just anecdotes; they are vivid, intimate archives of the city’s life. One of the first shifts I felt happened during interviews when we found ourselves talking about women’s roles, roles that are rarely acknowledged despite being fundamental to the social and economic life of Zarqa. After hours of fieldwork, I found myself saying: “I’ve come to appreciate my grandmother so much more.”

I never fully understood what my grandmother, Um Ammar, my father’s mother, carried on her shoulders. She was born in the 1940s and learned from her own mother how to farm, herd animals, and run a household. She cultivated wheat and barley, harvested by hand, and prepared food reserves for winter. My father told me how she used to wake before dawn to walk long distances to fetch water, gather firewood, bake on a metal griddle, and weave wool into tents. When she moved to Zarqa, she worked as a seamstress, stitched schoolbags, helped her neighbors, ran a trade with my grandfather, and bought three goats to secure milk for her children. Her life was marked by relentless effort and quiet generosity, never expecting recognition. I realized that women’s work, routinely overlooked or devalued, is the invisible foundation on which much of our social life stands. These are not just stories of the past; they are part of the living memory we’re trying to trace and honor through this project.

Another important reflection concerns my own position in the research. Being from the Bani Hassan tribe shaped how interviews unfolded. Sometimes, my presence enabled conversations that might not have happened otherwise. This came with a responsibility to listen with care and humility. I often found myself switching roles: interviewer, observer, insider. Each time I rethought what it means to belong to this city. The interviews were not just for collecting data; they became encounters that challenged how I saw myself and Zarqa. They nudged me to think beyond tribal affiliations and towards a broader, collective identity rooted in shared experiences.

At the beginning of the project, I mostly thought of myself as someone from Bani Hassan living in Zarqa. I hadn’t really considered what that meant in context. But with each interview, I started tracing the history of my own community, their role in farming and settling the area, and how they coexisted with Chechens, Palestinians, and others. This deepened my understanding of belonging. It is not a static label; it is a layered, evolving relationship grounded in history, knowledge, and mutual struggle. Belonging, I came to see, is made and remade through the everyday acts of building a city together.

The project pushed me to think more deeply about Zarqa. It is no longer just the place I live. It is a complex, living space that reveals itself through people’s stories. I feel more rooted here, but in a way that is outward-looking. My sense of responsibility now extends beyond family or tribe. I feel accountable to a wider social fabric, to a city shaped by many hands.